Discrimination and Opacity in Online Behavioral Advertising

Overview

To partly address people's concerns over web tracking, Google has created the Ad Settings webpage to provide information about and some choice over the profiles Google creates on users. We present AdFisher, an automated tool that explores how user behaviors, Google's ads, and Ad Settings interact. AdFisher can run browser-based experiments and analyze data using machine learning and significance tests. Our methodology uses a rigorous experimental design and statistical analysis to ensure the statistical soundness of our results. We use AdFisher to find that the Ad Settings was opaque about some features of a user's profile, that it does provide some choice on ads, and that these choices can lead to seemingly discriminatory ads. In particular, we found that visiting webpages associated with substance abuse changed the ads shown but not the settings page. We also found that setting the gender to female resulted in getting fewer instances of an ad related to high paying jobs than setting it to male. We cannot determine who caused these findings due to our limited visibility into the ad ecosystem, which includes Google, advertisers, websites, and users. Nevertheless, these results can form the starting point for deeper investigations by either the companies themselves or by regulatory bodies.Publications

Selected Press

Al Jazeera, CACM, CMU News, CMToday, Listening Brief, MIT Technology Review, New York Times: Upshot, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, TechCrunch, The Wall Street Journal, Washington Post: Intersect, Wired, and Yahoo Tech.

Other Mentions

ACLU, CIO, IAPP, The Guardian, The New Yorker, New York Times, ScienceNews, White House Report.

Key Findings

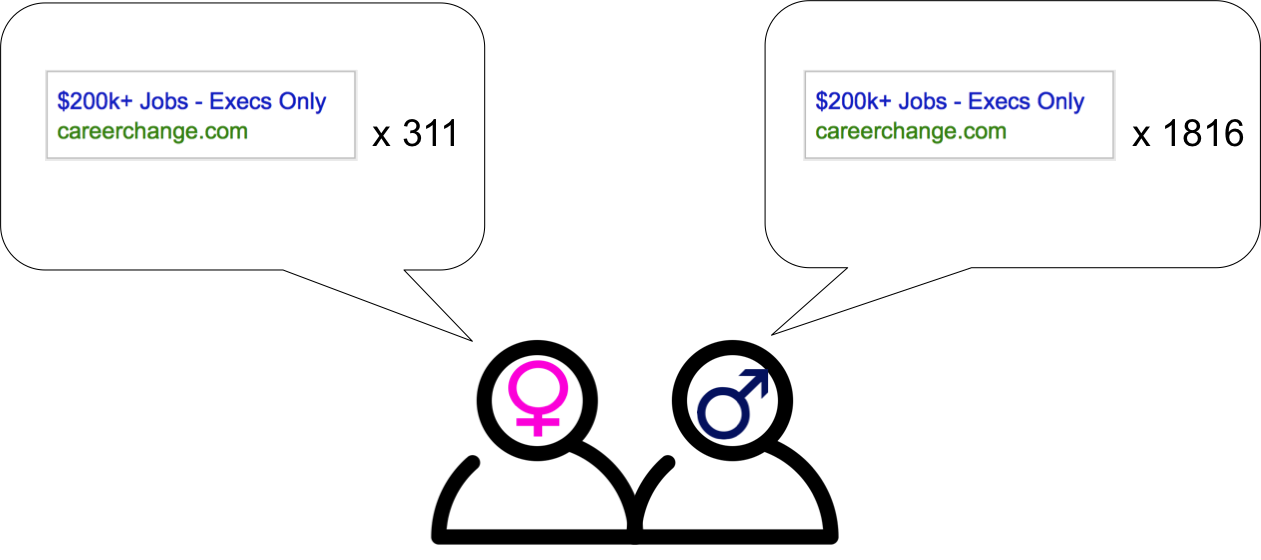

Discrimination

To study discrimination, we had AdFisher create 1000 fresh browser instances and assign them randomly to two groups. One group set their gender to male on Google's Ad Settings page, while the other set it to female. Then, all the browsers visited the top 100 websites for employment on Alexa. Thereafter, all the browsers collected the ads served by Google on the Times of India. The top two ads served to the male group was from a career coaching service called careerchange.com that promised high-paying executive level jobs. The top ad was served 1816 times to the male users, but only 311 times to the female users. Of the 500 simulated male users, 402 received the ad at least once, but only 60 female users received the same ad at least once.

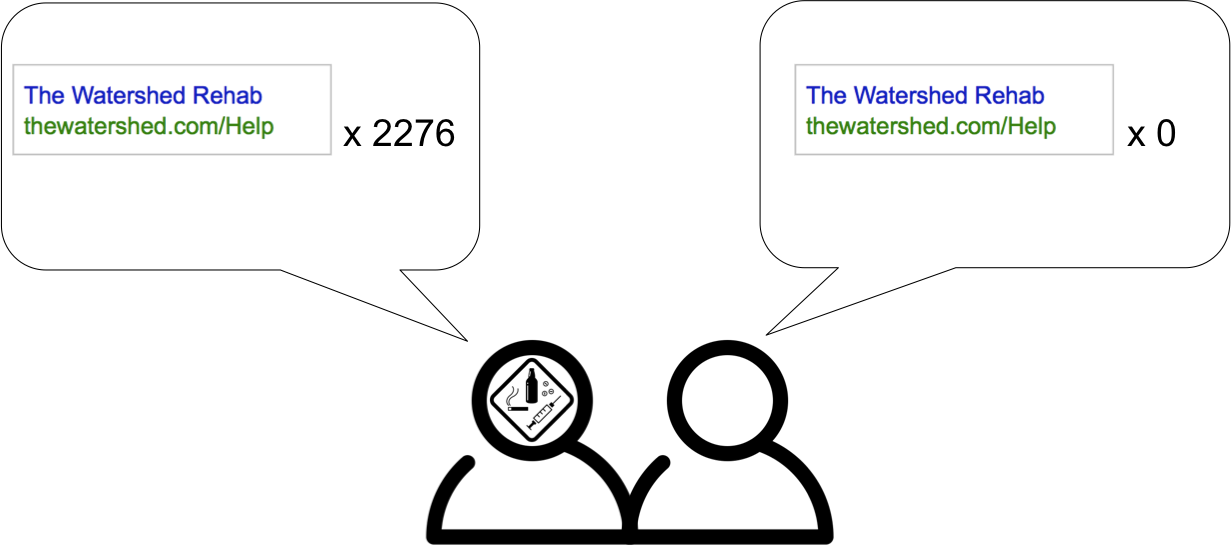

Opacity

To study opacity (a lack of transparency), we started with two groups of 500 fresh browser instances each. AdFisher drove one group to visit the top 100 websites for substance abuse on Alexa, while the other group idled. Thereafter, all the browsers collected the ads served by Google on the Times of India. The top three ads served to the substance abuse visitors were for an alcohol and drug rehabilitation center called the Watershed Rehab (www.thewatershed.com). The top three ads were served 2276, 362, and 771 times to the substance abuse visitors, but not a single time to the control group. However, there was no effect on the Ad Settings page - no demographics or interests were inferred for any browser in any group. We find this particular result even more concerning since it shows that the Google ad ecosystem is using health-related activities (visits to substance-abuse websites) to target ads.

You can find more details about our findings here.

Frequently Asked Questions

Have there been studies of this kind in the past?

Ours is the first study to demonstrate discrimination in online behavioral advertising by showing statistical significance. This is also the first study that shows Google's transparency tool (Ad Settings) can sometimes be opaque. The rigorous methodology behind our experimental design ensures that we find causal effects, not just correlations. Prior studies on behavioral marketing either do not show statistical significance, or make assumptions unlikely to hold in the ad ecosystem to obtain significance.

Who is responsible for the discrimination results?

We can think of a few reasons why the discrimination results may have appeared.

- The advertiser's targeting of the ad

- Google explicitly programing the system to show the ad less often to females

- Males and female consumers respond differently to ads and Google's targeting algorithm responds to the difference (e.g., Google learned that males are more likely to click on this ad than females are)

- More competition existing for advertising to females causing the advertiser to win fewer ad slots for females

- Some third party (e.g., a hacker) manipulating the ad ecosystem

- Some other reason we haven't thought of.

- Some combination of the above.

These further break down into subcases. For example, in (1), the advertiser might have been explicitly targeting on gender or on attributes that might be correlated with gender. Being on the outside, we don’t have enough visibility into the system to pinpoint the actual reason. Nevertheless, we find such differential treatment of male and female users for high-paying job opportunities concerning.

Who is responsible for the opacity results?

The opacity results may have appeared for reasons analogous to the ones mentioned above, but we suspect they were a result of remarketing. In remarketing, when a user visits an advertiser's website, the ad keeps following the user all over the Internet. We speculate remarketing to be the more likely reason among the two since thewatershed.com was among the substance-abuse websites visited prior to ad collection. Once again being on the outside, we cannot pinpoint the actual reason.

Have you conveyed your findings to Google?

We informed some researchers at Google about our findings, but did not receive an official response from them. Google however responded to a journalist at the Pittsburgh Post Gazette stating it’s possible that women saw a greater variety of display ads overall because advertisers generally target women as a demographic more (Reason #4 from above). Additionally, in response to a MIT Technology Review journalist, they said Advertisers can choose to target the audience they want to reach, and we have policies that guide the type of interest-based ads that are allowed

(Reason #1 from above).

Have you conveyed your findings to the Barrett Group?

We did not contact the Barrett Group. However, when a journalist at the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette contacted them, they did issue a statement. An excerpt from the article states

Barrett Group president Waffles Pi Natusch said he’s not sure how the ads ended up skewing so heavily toward men but noted some of the company’s ad preferences might push Google’s algorithms in that direction. The company generally seeks out individuals with executive-level experience who are older than 45 years and earn more than $100,000 per year.

Read the full article here.

What are the implications of the discrimination results?

When the ad selection process is data-driven and algorithms do nothing to prevent discriminatory inputs from affecting results, algorithms reflect whatever is fed in including human prejudices. Such reflections can further reinforce existing stereotypes, leading to more skewed input data. The algorithms are unaware of fairness or social norms. As more and more algorithms are being used to make important decisions like loan approvals, insurance rates, etc., it is important that the algorithms are aware of such social and ethical values. We carry out a legal analysis of our results and find that an ad platform (in this case, Google) may be held legally liable for serving discriminatory ads under certain scenarios in this paper.

Has anything changed as a result of these findings?

As outsiders, we found that Google made it more difficult to access all features of the Ad Settings tool. Without signing in, users can no longer view or edit demographics and inferred interests. While this has made re-running similar experiments harder, it is unclear whether they have made algorithmic or policy changes internally to prevent such discrimination from re-ocurring. We don't have any reason to believe so, since we were able to use Google's ad platform to target and exclude employment and housing ads based on gender by posing as advertisers in late 2017. These results are available here

Why are these findings important?

Our experiments demonstrate the existence of discrimination and opacity in complex environments involving data-driven algorithms and human actors. Results such as ours using external oversight tools like AdFisher can provide a starting point for further investigations by companies that run ad networks or by regulatory agencies with oversight powers. We are also interested in collaborating with companies that operate on personal information to create oversight tools for internal use.